In collaboration with Eden Hoang

“People’s connection to space is rich and complex and includes strands of individual and collective memory, history, culture, ownership, custodianship, production, aesthetic appreciation, and so on. As such, the public realm can be understood as a tapestry of individual and incomplete narratives of the past, present and future.”

- (Grabasch & Firns 2013, 13)

The depictions of the architecture and landscape profession are heavily romanticised through media, writing and photography. From written texts such as ‘The Fountain Head’ to media portrayals in ‘How I Met Your Mother’ and ‘Parks and Recreation’ the representation is undoubtedly palpable, albeit tedious.

Especially when those around us discovered what we were studying, they would jokingly ask:

Can you design a house for me?

Can you design a garden for me?

Understanding the difference between architecture and landscape architecture can be narrowed down to the built form and the existing site. Prior to our education in the field, there were assumptions that we would be designing a building, or anything in-between buildings respectively given the additional term added to the occupation.

There is a challenge for us to explain that architecture and landscape architecture are just beyond the infrastructure and the existing site, respectively. By considering the context, history, etcetera, some similarities blurred the relationship between the obvious and the unknown - thus resulting in us succumbing to using the simplified description.

The stereotype of landscape architecture often can be confused with urban planning due to the broad concept of ‘landscape’ itself. While there can be some level of residential garden design involved in landscape architecture (most common spaces such as shared courtyards, rooftop gardens, townhouse neighbourhood garden designs), we usually design for the public realm at a multitude of scales (from urban street parks to rejuvenating degraded landscapes). To summarise, the role of a landscape architect begins in “creating spaces within our natural and built environments that respect and enhance our interaction with landscape.” (Kombol 2015, 8) The study of landscape architecture teaches the necessary skills that influence the foundation and analysis of each project design.

Environmental work focuses on the examination of existing site conditions; often heading out onto site to identify plants, using a dumpy level to measure spot levels, or even how the space is currently being occupied.

Communications allow the exploration of different representation styles, experimenting with different programs such as AutoCAD, Rhino, or Grasshopper.

Theoretical frameworks involved learning about existing projects designed by landscape architects and analysing their functionality and form. Concepts of architecture history were also learnt - Modernism, Post-modernism, and Phenomenology.

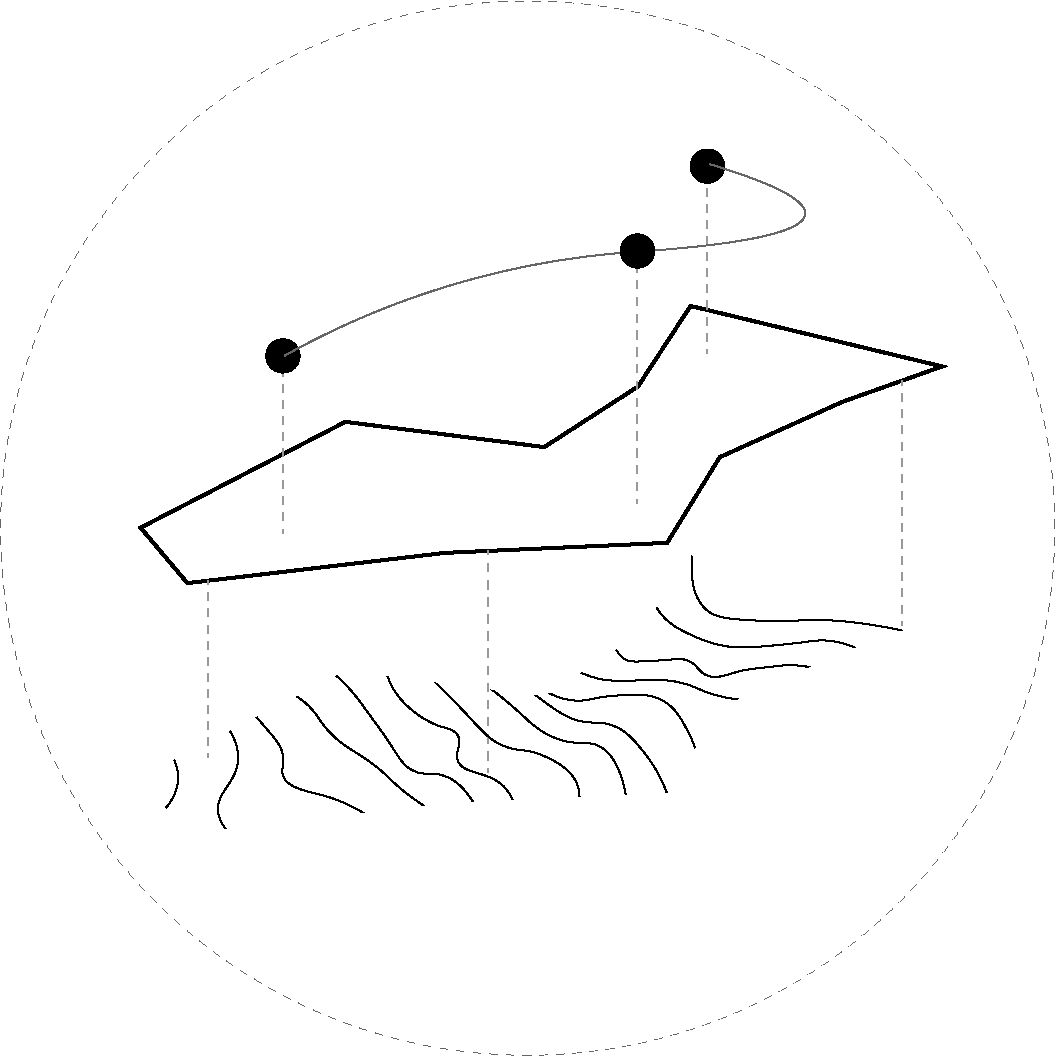

In professional practice, the skills learnt in university contribute to the concept phase of projects. The concept phase begins with a brief collaborated with the client, which from there, concept designs are brainstormed and reiterated until all points within the brief are met. Packages are then compiled with a plan, visual interpretations of the space, precedent images, plant and material palettes to help convey the design to the client.

After the concept is presented to the client, any issues flagged within the design are amended, and the design development phase begins. This usually includes creating surface treatment plans, set out plans, drawing details, planting plans, planting schedules - all necessary documents needed for contractors to construct the project.

Similarly, studying architecture encompasses the theoretical knowledge and practical work. It was a process in understanding the theories that lead to the composition of the building. Our course is broken down with studio being the core supported by an elective and one of the following: professional practice, communication or materiality.

Jumping into architecture with the ambition of designing a monumental icon was utterly removed when we were tasked with creating abstract models drawn from observing the negative space. It was learning to appreciate the conceptual lens of architecture, understanding the importance of spatial choreography and the impact it has on designated user groups. Architecture can be argued as a curation of space. Establishing the area does require a good understanding of the context of the design, much like landscape architecture; however, done in a broader context, instead concentrating each area in greater detail. (Hence the importance of collaborating with other professions)

One of the most exhausting obligations of the architect that many are unaware of is the amount of communication that pass through their channel. Majority of the time, we have a responsibility to ensure that all the elements that have been pulled together and is relayed clearly to the client. While it indicates that the architect is the project manager, there is a frustrating fear that comments could be lost in translation. Of course, it is understandable that many would rather have a team to take charge. However, this closes the opportunity for the audience to gain value on the specificities of each side that has placed effort to ensure the collaboration would happen.

“(architecture has) a rigorous conversation with nature… (and) interrupts nature”

- Glenn Murcutt and Sean Godsell, Conversation with Sean Godsell and Glenn Murcutt at Hill of Content Bookshop, Melbourne, October 31, 2019

There is interdisciplinary collaboration involved between landscape architects, architects (also to include planners, developers and landowners), though more often than not, landscape architecture is seen as an afterthought within the design process. For example, adding a strip of lawn with trees as a finishing touch. There are many cases where problems have arisen, which could have been avoided if a dialogue between different disciplines was put into action earlier, as the expertise of multiple perspectives is better than one. As designers, it is critical not only to form ideas during the beginning of a concept but also to continue the communication as design works within a continuous cycle of iterations.

Given that we study similar principles, we must look at architecture and landscape uniformly rather than staged progress. Nature is an existing foundation to build on, and architecture forms ‘a rigorous conversation’ as the existence itself ‘interrupts nature’. Despite the workflow, architecture is predominantly a linear process, the straightforwardness oversees the blind spots of potential flaws – only to be discovered later. Landscape and architecture shouldn’t be mutually exclusive in the process, but rather should be inclusive from the very start.

References:

Meaghan Kombol. 2015. 30|30 Landscape Architecture. 1st ed. London, N1 & New York, NY, Phaidon Press.

Greg Grabasch and Daniel Firns. 2013. “Connecting People and Place.” Landscape Architecture Australia No/139, August: 12-14

In response to:

Li, Qidi. 2019. “Why Landscape Architecture”. Filmed on 12 October 2019, Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/tv/B3glrLKpk49/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link. Accessed 12 October 2019 and 5 January 2020.

About Eden Hoang

Eden Hoang graduated from RMIT in the Bachelor of Landscape Architectural Design. At the moment she’s currently working in a small design firm where she gets to expand her plant knowledge with every project and play with the office dogs. Her interest in landscape architecture stemmed from her love of drawing, photography, and science. Within landscape architecture, Eden hopes to work on projects exploring the possibilities of urban permaculture and spatial narratives.

You can find out more about her on: